12th Feb 2026

From Hobby to Credit: The Official Certification Journey of Guzheng Education in Canada

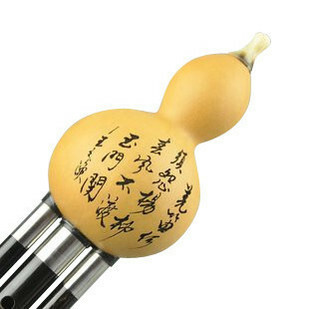

The sound of the guzheng is no longer just a nostalgic echo in Chinese-Canadian households during festivals. It has quietly entered classrooms, graced stages, and even become an official course on high school transcripts. Behind this is a long journey from a folk interest to institutional recognition. The guzheng is carving out its own path of localization in this multicultural land.

The formalization of guzheng education in Canada began in 2006 when the Central Conservatory of Music's overseas grading system was introduced to provide a systematic evaluation standard for children learning Chinese folk music abroad. Just one year later, the Ministry of Education of British Columbia made a landmark decision: officially recognizing this grading system as a basis for credits in extracurricular art courses. This was the first and remains the only Chinese folk music grading system officially certified by a provincial education department in Canada.

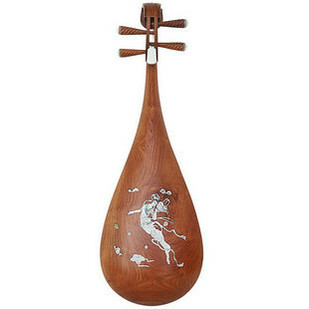

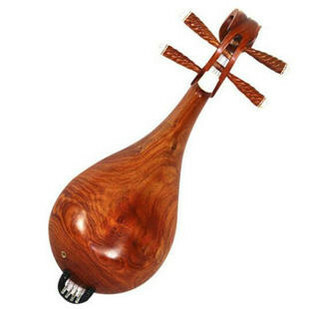

Under this system, the guzheng, along with traditional instruments like the erhu and pipa, was included in the list of projects that could earn high school credits. Students who pass the grade seven or higher performance exam and complete the corresponding music theory assessment can earn up to eight high school credits. These credits not only count towards graduation requirements but also for university applications, truly transforming playing the guzheng from a hobby into a part of academic planning. This policy broke the long-standing dominance of Western instruments in art education and gave Eastern instruments their first equal footing in the mainstream educational framework.

This mechanism has led the previously fragmented interest class-style teaching towards a standardized and sustainable development path. However, challenges remain. There is a shortage of qualified professional teachers, and original teaching materials suitable for local students are still scarce. The recognition of the guzheng among non-Chinese communities also needs improvement. But the good news is that changes are already underway. More and more art departments in universities are inviting folk musicians to give lectures, and local creators are attempting to combine the guzheng with jazz, electronic music, and even improvisational theater, exploring the boundaries of sound.

From a background accompaniment in Chinese New Year celebrations to independent performances at campus art exhibitions, the guzheng's identity in Canada is undergoing a profound transformation. It is no longer merely a vessel of nostalgia but has become a bridge for cross-cultural exchange and a carrier for artistic growth.

From a symbol of homesickness to a credit-bearing course, from a community hobby to an official curriculum, the transformation of guzheng education in Canada is a vivid example of the overseas spread of Chinese culture. It proves that traditional instruments can only truly take root in foreign lands by integrating into local education systems and meeting the needs of mainstream society, allowing the resonant strings of the East to play a lasting and resounding melody in multicultural Canada.