14th Jan 2026

The Eastward Journey of the Guqin: Its Spread and Development in Japan

As a carrier of Chinese cultural heritage, the guqin's eastward transmission to Japan can be traced back to the Tang Dynasty in the 7th and 8th centuries. However, its development path in Japan was quite different from that in China, forming a unique process of "introduction, disappearance, and reintroduction".

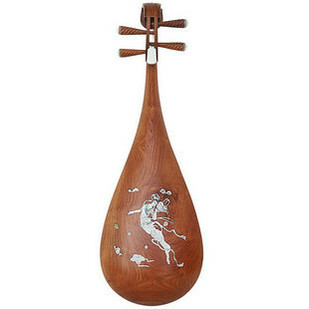

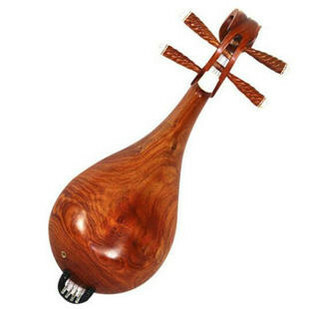

The Tang Dynasty marked the initial stage of the guqin's introduction to Japan. During this period, Sino-Japanese exchanges were unprecedentedly prosperous. From 630 AD, Japan sent over ten missions to Tang China. These envoys not only brought back Tang poetry, calligraphy, and paintings but also introduced guqin instruments, scores, and related literature to Japan. To this day, several Tang Dynasty guqins are still preserved in the Shosoin Repository and Horyuji Temple in Japan, with the most famous being the gold-inlaid guqin, which serves as direct evidence of the eastward spread of the guqin. However, the guqin did not gain popularity among the Japanese court or the common people. By the Heian period, with the maturation of the court music system, the guzheng and pipa became more favored, so the guqin gradually fell out of favor and was eventually lost.

The second introduction of the guqin to Japan began with a cultural migration in the early Qing Dynasty. In 1677, the Chinese monk Donggao Xinyue fled to Japan to escape the chaos of war. He not only brought five guqins and a series of scores with him, but also introduced his superb guqin skills to Japan. During his stay in Japan, Donggao Xinyue widely recruited disciples and systematically taught them guqin playing techniques and theoretical knowledge. He is thus revered by later generations as the "re-founder of Japanese guqin studies". Unfortunately, the refined and reserved aesthetic of the guqin did not align with the bright and ornate tastes favored by the Japanese aristocracy after the Heian period. Despite Donggao Xinyue's efforts to promote guqin culture, the instrument never gained a broad popular base and was only passed down within a small circle of scholars, literati, and art enthusiasts.

Today, the guqin remains a niche field in Japan, sustained by local guqin societies and dedicated enthusiasts. However, in recent years, the increasingly close cultural exchanges between China and Japan have injected new vitality into the spread of the guqin in Japan. More and more Chinese guqin masters have traveled to Japan to hold concerts and give lessons, allowing the Japanese public to experience the unique charm of the guqin up close. At the same time, many scholars like the Dutch sinologist Robert van Gulik have devoted themselves to studying guqin culture and systematically documenting its transmission history in Japan. Their works not only deepen the international community's understanding of the guqin but also promote this ancient instrument to cross borders and become an important cultural link between China and Japan.

The journey of the guqin to the east, carrying the cultural winds of a thousand years, also witnesses the delicate interweaving of the civilizations of China and Japan. It did not grow into a towering tree on foreign soil but has persisted in a niche yet resilient manner, becoming a cultural imprint that transcends mountains and seas.